The New York Times New York, New York Saturday, August 28, 1965 - Page 19

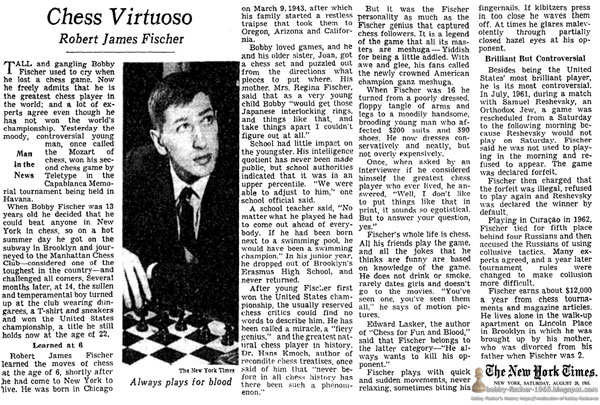

Chess Virtuoso: Robert James Fischer

TALL and gangling Bobby used to cry when he lost a chess game. Now he freely admits that he is the greatest chess player in the world; and a lot of experts agree even though he has not won the world's championship. Yesterday the moody, controversial young man, once called the Mozart of chess, won his second chess game by Teletype in the Capablanca Memorial tournament being held in Havana.

When Bobby Fischer was 13 years old he decided that he could beat anyone in New York in chess, so on a hot summer day he got on the subway in Brooklyn and journeyed to the Manhattan Chess Club—considered one of the toughest in the country—and challenged all comers. Several months later, at 14, the sullen and temperamental boy turned up at the club wearing dungarees, a T-shirt and sneakers and won the United States championship, a title he still holds now at the age of 2.

Learned at 6

Robert James Fischer learned the moves of chess at the age of 6, shortly after he had come to New York to live. He was born in Chicago on March 9, 1943, after which his family started a restless traipse that took them to Oregon, Arizona and California.

Bobby loved games, and he and his older sister, Joan, got a chess set and puzzled out from the directions what pieces to put where. His mother. Mrs. Regina Fischer, said that as a very young child Bobby “would get those Japanese interlocking rings, and things like that, and take things apart I couldn't figure out at all.”

School had little impact on the youngster. His intelligence quotient has never been made public, but school authorities indicated that it was in an upper percentile. “We were able to adjust to him,” one school official said.

A school teacher said, “No matter what he played he had to come out ahead of everybody. If he had been born next to a swimming pool, he would have been a swimming champion.” In his junior year, he dropped out of Brooklyn's Erasmus High School, and never returned.

After young Fischer first won the United States championship, the usually reserved chess critics could find no words to describe him. He has been called a miracle, a “fiery genius,” and the greatest natural chess player in history. Dr. Hans Kmoch, author of recondite chess treatises, once said of him that “never before in all chess history has there been such a phenomenon.”

But it was the Fischer personality as much as the Fischer genius that captured chess followers. It is a legend of the game that all its masters are meshuga — Yiddish for being a little addled. With awe and glee, his fans called the newly crowned American champion ganz meshuga.

When Fischer was 16 he turned from a poorly dressed, floppy tangle of arms and legs to a moodily handsome, brooding young man who affected $200 suits and $90 shoes. He now dresses conservatively and neatly, but not overly expensively.

Once, when asked by an interviewer if he considered himself the greatest chess player who ever lived, he answered, “Well, I don't like to put things like that in print, it sounds so egotistical. But to answer your question, yes.” Fischer's whole life is chess. All his friends play the game, and all the jokes that he thinks are funny are based on knowledge of the game. He does not drink or smoke, rarely dates girls and doesn't go to the movies. “You've seen one, you've seen them all:” he says of motion pictures.

Edward Lasker, the author of “Chess for Fun and Blood,” said that Fischer belongs to the latter category—“He always wants to kill his opponent.” Fischer plays with quick and sudden movements, never relaxing, sometimes biting his

fingernails. If kibitzers press in too close he waves them off. At times he glares malevolently through partially closed hazel eyes at his opponent.

Brilliant But Controversial

Besides being the United States' most brilliant player, he is its most controversial. In July, 1961, during a match with Samuel Reshevsky, an Orthodox Jew, a game was rescheduled from a Saturday to the following morning because Reshevsky would not play on Saturday. Fischer said he was not used to playing in the morning and refused to appear. The game was declared forfeit.

Fischer then charged that the forfeit was illegal, refused to play again and Reshevsky was declared the winner by default.

Playing in Curacao in 1962, Fischer tied for fifth place behind four Russians and then accused the Russians of using collusive tactics. Many experts agreed, and a year later tournament rules were changed to make collusion more difficult.

Fischer earns about $12,000 a year from chess tournaments and magazine articles. He lives alone in the walk-up apartment on Lincoln Place in Brooklyn in which he was brought up by his mother, who was divorced from his father when Fischer was 2.