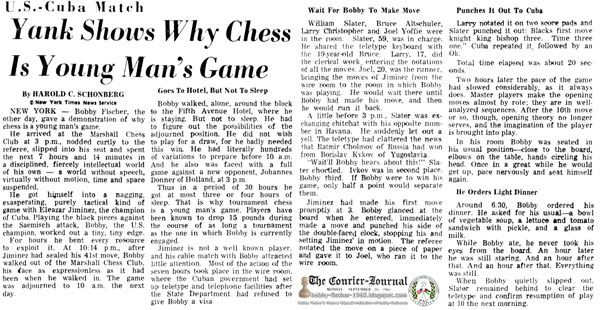

The Courier-Journal Louisville, Kentucky Monday, September 20, 1965 - Page 11

U.S.-Cuba Match - Yank Shows Why Chess Is Young Man's Game

By Harold C. Schonberg New York Times News Service

New York — Bobby Fischer, the other day, gave a demonstration of why chess is a young man's game.

He arrived at the Marshall Chess Club at 3 p.m., nodded curtly to the referee, slipped into his seat and spent the next 7 hours and 14 minutes in a disciplined, fiercely intellectual world of his own — a world without speech, virtually without motion, time and space suspended.

He got himself into a nagging, exasperating, purely tactical kind of game with Eleazar Jiminez, the champion of Cuba. Playing the black pieces against the Saemisch attack, Bobby, the U.S. champion, worked out a tiny, tiny edge.

For hours he bent every resource to exploit it. At 10:14 p.m., after Jiminez had sealed his 41st move, Bobby walked out of the Marshall Chess Club, his face as expressionless as it had been when he walked in. The game was adjourned to 10 a.m, the next day.

Goes To Hotel, But Not To Sleep

Bobby walked, alone, around the block to the Fifth Avenue Hotel, where he is staying. But not to sleep. He had to figure out the possibilities of the adjourned position. He did not wish to play for a draw, for he badly needed this win. He had literally hundreds of variations to prepare before 10 a.m. And he also was faced with a full game against a new opponent, Johannes Donner of Holland, at 3 p.m.

Thus in a period of 30 hours he got at most three or four hours of sleep. That is why tournament chess is a young man's game. Players have been known to drop 15 pounds during the course of as long a tournament as the one in which Bobby is currently engaged.

Jiminez is not a well known player, and his cable match with Bobby attracted little attention. Most of the action of the seven hours took place in the wire room, where the Cuban government had set up teletype and telephone facilities after the State Department had refused to give Bobby a visa.

Wait For Bobby To Make Move

William Slater, Bruce Altschuler, Larry Christopher and Joel Yoffie were in the room. Slater, 59, was in charge. He shared the teletype keyboard with the 19-year-old Bruce. Larry, 17, did the clerical work, entering the notations of all the moves. Joel, 20, was the runner, bringing the moves of Jiminez from the wire room to the room in which Bobby was playing. He would wait there until Bobby had made his move, and then he would run it back.

A little before 3 p.m., Slater was exchanging chitchat with his opposite number in Havana. He suddenly let out a yell. The teletype had clattered the news that Ratmir Cholmov of Russia had won from Borislav Ivkov of Yugoslavia.

“Wait'll Bobby hears about this!” Slater chortled. Ivkov was in second place, Bobby third. If Bobby were to win his game, only half a point would separate them.

Jiminez had made his first move promptly at 3. Bobby glanced at the board when he entered, immediately made a move and punched his side of the double-faced clock, stopping his and setting Jiminez' in motion. The referee notated the move on a piece of paper and gave it to Joel, who ran it to the wire room.

Punches It Out To Cuba

Larry notated it on two score pads and Slater punched it out: “Blacks first move knight king bishop three. Time three one.” Cuba repeated it, followed by an Ok.

Total time elapsed was about 20 seconds.

Two hours later the pace of the game had slowed considerably, as it always does. Master players make the opening moves almost by rote; they are in well-analyzed sequences. After the 10th move or so, though, opening theory no longer serves, and the imagination of the player is brought into play.

In his room Bobby was seated in his usual position—close to the board, elbows on the table, hands circling his head. Once in a great while he would get up, pace nervously and seat himself again.

He Orders Light Dinner

Around 6:30, Bobby ordered his dinner. He asked for his usual—a bowl of vegetable soup, a lettuce and tomato sandwich with pickle, and a glass of milk.

While Bobby ate, he never took his eyes from the board. An hour later he was still staring. And an hour after that. And an hour after that. Everything was still.

When Bobby quietly slipped out, Slater remained behind to clear the teletype and confirm resumption of play at 10 the next morning.